1 Introduction

As the future of urban sound research and practice moves toward a more holistic soundscape focus, the ability to affect change at large scales and in a wide range of projects will require that familiar engineering tools and approaches can be applied to soundscape design. When attempting to apply soundscape in practice in the built environment, it becomes apparent that a predictive model of the users’ perceptual response to the acoustic environment is necessary. Whether to determine the impact of a design change, or to integrate a large scale data at neighbourhood and city levels, a mathematical model of the interacting factors will form a vital component of the implementation of the soundscape approach.

Current methods of assessing soundscapes are generally limited to a post hoc assessment of the existing environment, where users of the space in question are surveyed regarding their experience of the acoustic environment (Engel et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2018; Ba and Kang 2019). While this approach has proved useful in identifying the impacts of an existing environment, designers require the ability to predict how a change or proposed design will impact the soundscape of the space, before its implementation. To this end, a model that is built on measurable or estimate-able quantities of the environment would represent a leap forward in the ability to design soundscapes and to assess their broad impacts on health and wellbeing.

We will begin by outlining the use cases of predictive soundscape models and how they are necessary for certain applications. From the desired use cases, we will then outline a framework within which practical predictive models can be developed.

2 Defining what a predictive soundscape model is

Aletta, Kang, and Axelsson (2016) provide a review of the soundscape descriptors and indicators commonly used in soundscape research and outlines an initial framework for developing predictive soundscape models. In their review, the authors identified eight potential soundscape descriptors, including perceived affective quality (Axelsson, Nilsson, and Berglund 2010), restorativeness (Payne 2013), etc. Similarly, the authors identified a range of potential indicators used to characterise the acoustic environment, including environmental acoustics indicators such as L_{Aeq}, L_{Ceq} − L_{Aeq} and psychoacoustic indicators such as Loudness (N_5) and Sharpness (S).

However, it is noted that several studies show that no single psychoacoustic indicator alone can explain the variation in soundscape responses (as expressed via the descriptors) (e.g. (Persson Waye and Öhrström 2002)). The goal of statistical modelling, therefore is to create a more complex and complete representation of the relationship between soundscape indicators and descriptors, beyond what any single indicator could achieve.

Figure 1 shows a conceptual view of this relationship. We start with soundscape indicators, which characterise the physical and contextual environment to which the listener is exposed. This can be broken down into sonic features (e.g. the acoustical features listed above) and characteristics of the space itself (e.g. the amount of visible sky, the intended use-case of the space, how crowded the space is, etc.). In order to translate from the physical inputs to an expressed description of the soundscape perception, we introduce the concept of a perceptual mapping (Lionello 2021). This mapping represents a simplified idea of how each individual’s brain processes the inputs from the soundscape which they experience, forms a perception, and finally expresses that perception through their description of the soundscape. For our purposes, this perceptual mapping is treated as essentially a black box mapping inputs to outputs. It can be conceived of as a network of weights in which certain characteristics of the sound may have different weights and directions depending on the context, through which all of the inputs are processed, resulting in the soundscape rating. Conceptually, this perceptual mapping – the pathways and weightings through which the inputs are processed before being expressed as a perceptual descriptor – is established prior to an individual’s exposure to the soundscape in question.

It should be made clear that this represents a very simplified view of how a soundscape perception is formed, however it provides a useful conceptual framework for the purposes of understanding and modelling how someone’s perception forms in response to their exposure to a space. One way to consider the function of a statistical model of soundscape perception is as replicating the perceptual mapping between soundscape indicators and descriptors (Lionello 2021). As a person experiences an urban space, they are exposed to an array of physical inputs, these are then processed by the listener through their own personal experience and mapped to their perception of that space. This perception is then expressed through their description of this experience of the soundscape. It is this mapping of physical inputs to perceptual description which the statistical model aims to reflect. The most successful model would then accurately replicate the general perceptual mapping across the population.

3 Applications in design and mapping

The soundscape approach faces several challenges in practical applications which are unaddressed by current assessment methods, but which may be solved through the development of a predictive modelling framework. The first of these challenges is predicting how a change in an existing sound environment will be reflected in the soundscape perception. While it is possible in this scenario to measure the existing soundscape perception via questionnaire surveys, if a change is then introduced to the acoustic environment, it is so far impossible to say what the resulting soundscape change would be. This question relates strongly to the idea of soundscape interventions; where a particular noise pollution challenge is addressed by introducing more pleasant sounds (e.g. a water feature), following the soundscape principle of treating sound as a resource (Lavia et al. 2016; Moshona et al. 2022). Predicting how much a particular intervention would improve the soundscape (or, indeed whether it would improve at all) is not yet possible with the retrospective methods available.

Several studies have attempted to address this gap by developing machine learning or statistical models of soundscape perception which are focussed on prediction, rather than inference. An array of modelling techniques are used, with linear regression being the most common (Lionello, Aletta, and Kang 2020), and also including artificial neural networks (ANN) (Puyana Romero et al. 2016; Yu and Kang 2009) and support vector regression (SVR) (Fan, Thorogood, and Pasquier 2016, 2017; Giannakopoulos, Orfanidi, and Perantonis 2019). However, these studies have focussed primarily on using these models to investigate the constructs of soundscape perception, with few efforts to put the models themselves to use. Mitchell et al. (2021) attempted to address this by both developing a predictive model and applying it to an applied scenario where traditional assessment methods were impractical. In a unique application, Ooi et al. (2022) created a predictive model of soundscape pleasantness which fed an automated and reactive soundscape enhancement system (Watcharasupat et al. 2022).

Retrospective methods also struggle to capture the dynamics of the soundscape in a space. Whether through the narrative interview method of ISO/TS 12913-2 (ISO/TS 12913-2:2018 2018), through soundwalks, or through in situ questionnaires (Mitchell et al. 2020), only the soundscape during the particular period which the researchers are actively investigating is captured. This makes it very difficult to determine diurnal, seasonal, or yearly patterns of the soundscape. These patterns may be driven by corresponding diurnal, seasonal, or yearly patterns in the acoustic or visual environment, or by variations in how people process and respond to the sound at different times of day/season/year. Currently the only way to investigate any of these patterns is through repeated surveys. Predictive modelling, on the other hand, could allow a trained soundscape model to be paired with longterm monitoring methods to track how a soundscape perception may change in response to changes in the acoustic environment.

Similarly, a move towards modelling methods based on objective and/or measurable factors would facilitate the application of mapping in soundscape. While noise maps have become common in urban noise research and legislation (EEA 2020; Gasco et al. 2020), they can be difficult to translate into a soundscape approach. The Environmental Noise Directive (END) (European Union 2002), first implemented in 2002, is the main EU instrument to identify noise pollution impacts and track urban noise levels across the EU. Its goals were to determine the population’s exposure to environmental noise, make information on environmental noise available to the public, and prevent and reduce environmental noise and its effects. In general, noise maps are based on modelled traffic flows, from which decibel levels are extrapolated and mapped, although interpolation and mobile measurement methods have also been recently developed (see Aumond, Jacquesson, and Can 2018). Alternatively, they can be produced using longterm SLMs or sensor networks. While these methods have significant utility for tracking increases in urban noise levels and are important for determining the health and societal impacts of noise on a large scale, their restricted focus on noise levels alone limits their scope and reduces the potential for identifying more nuanced health and psychological effects of urban sound.

Several studies have attempted to bring soundscape to urban noise mapping. The most notable of these attempts (Aumond, Jacquesson, and Can 2018; Aletta and Kang 2015; Hong and Jeon 2017; Kang and Aletta 2018) bring new, more sophisticated methods for mapping urban sound (not just noise levels). For instance, all four present methods which map the relative level of various sound sources, producing maps of the spatial distribution of bird sounds, human voices, water sounds, etc. In Aletta and Kang (2015) and Hong and Jeon (2017) the mapping relied on soundscape surveys conducted in public spaces, then used interpolation methods and basic relationships to the measured noise levels to generate a map of the perceived soundscape over the entire study space. Kang et al. (2018), after starting with survey responses, attempted to create a prediction methods which relied only on the audio recordings made in the space to create visual maps of the predicted soundscape perception (i.e. the perceptual attributes ’pleasant’, ’calm’, ’eventful’, ’annoying’, ’chaotic’, ’monotonous’). According to the authors, the prediction and mapping model would follow three steps: (1) sound sources recognition and profiling, (2) prediction of the soundscape’s perceptual attributes, and (3) implementation of soundscape maps. Unfortunately, from the paper, it appears that the prediction model results were not actually used for the mapping and, again, the survey responses from 21 respondents were interpolated to create the soundscape map. Their results indicated how a predictive model could have been slotted into a mapping use-case, but this was limited by (1) the relatively poor predictive performance for several of the attributes, (2) the inability to automatically recognise sound sources, and (3) a very limited dataset in terms of sample size and variety of locations.

While the connection is not made to perception, Aumond, Jacquesson, and Can (2018) focussed on creating sound maps which can reflect the pattern of sound source emergences over time within a city. By stochastically activating varying sound sources across their map, they could map the percentage of time when a sound source emerges from the overall complex sound environment. If a predictive soundscape model which incorporates sound source information can be developed, then the same procedure which led to their sound source emergence maps could also feed the soundscape model, resulting in a map of predicted perception over time.

Urban scale noise mapping and its implementation at the international level has been crucial in highlighting the health impacts of urban noise and in providing evidence for the negative cost of excess noise. Traffic flow models of noise, large community noise surveys, and policy requirements to track noise levels have all been necessary to reveal these impacts. By creating predictive soundscape models, combined with new tools and sensing capabilities from smart city efforts, we can bring soundscape into these same realms. Without this, these large-scale impact studies will be limited to valuing the negative cost of urban noise, missing the potential value of positive soundscapes. By bringing perception-based practice to the same scale and type of evidence, we can expand urban sound research to consider a holistic view of urban spaces and their impacts.

The broader use-case and need for such soundscape models and maps was recently highlighted by Jiang et al. (2022), which opens the discussion for how the value and impact of soundscapes should be measured and what tools are needed to enable the valuation of policy interventions for soundscapes. In response to Question 5, “What soundscape metrics and data will be needed?”, the authors make clear the necessity of predictive soundscape models: “Quantitative soundscape metrics that link subjective perceptions to objective acoustic and contextual factors will be needed, to enable monetisation while at the same time account for the perception-based nature of soundscape.” In addition, the authors make a strong case for the need for soundscape indices: “Despite the varied requirements for soundscape metrics and data between and even within valuation methods, a standardised metric or set of metrics, such as dB in noise valuation [. . . ] will allow comparison and integration of different studies and building compatible evidence bases.”

4 The Predictive Soundscape Model Framework

Several forms and iterations of predictive models have been developed (Lionello, Aletta, and Kang 2020) and more recently they have been put to use in real-world use cases (Mitchell et al. 2021; Watcharasupat et al. 2022). To improve on these models and make them into a useful engineering tool, we should establish a framework of overarching goals for models to achieve and the resulting development constraints. In general, the goals we define are related to how we might wish for models to be used and deployed, while the constraints are practical limitations which may make the performance of a given model less than ideal, but are necessary to achieve the deployment goals.

4.1 Goals

Before defining what form a general practical predictive model should take, we first need to make clear what the goals of such a model are, as derived from the preceding discussion laying out why predictive models are needed in soundscape.

Accuracy – First, that it to a reasonable extent is successful in predicting the collective perception (see Mitchell, Aletta, and Kang 2022) of a soundscape. It should succeed at both indicating the central tendency of the soundscape perception, but importantly it should also inform the likely spread of perception among the population. The outcome of the predictive model should not be focussed on predicting an individual assessment; the goal is not the predict the perception of any specific individual, but to reflect the public’s perception of a public space. In other words, ideally the model will result in an accurate distribution of soundscape perceptions for the target population.

Automation – Second, that it can be implemented automatically. Once an initial setup is performed, such as identifying what location the measurements are conducted in, the model should be capable of moving from recorded information to predicted soundscape distribution without human intervention. We need soundscape assessments to be able to be performed instrumentally. This enables it to be applied to unmanned uses, such as smart city sensors and soundscape mapping. It is impractical to conduct soundscape surveys or soundwalks in every location we wish to map and certainly not when we wish to see how these locations change over longer periods of time. A predictive model should allow us to survey these soundscapes remotely in order to extend soundscape to city-scale assessments.

Comparisons – Third, the model should enable us to test, score, and compare proposed interventions. In a design context, it is crucial that various strategies and interventions can be tested and that the influencing factors can be identified. The model should assist the user in highlighting what factor is limiting the success of a soundscape, spark ideas for how to address it, and allow these ideas to be tested. Several other useful features of predictive soundscape models arise out of these goals and will be discussed later, but these form the core goals of the framework.

4.2 Constraints

If we accept that predictive models are necessary to advance a more holistic approach to urban sound in smart cities, we must then define the constraints of such a model. The goal here is to define a framework for what is needed from a future model intended to be used in a smart city sensors, soundscape mapping, or urban design context.

Inputs – The first constraint is that the model must be based on measurable factors. By this, we mean that the data which eventually feeds into the predictive model should be collected via sensor measurements of one sort or another; this could be acoustic sound level measurements or recordings, environmental measurements, video recordings, or GIS measurements, etc. What it certainly cannot include is perceptual data. This is strictly a practical constraint – for a predictive model designed to be used in practice, there is no justification to include other perceptual factors, such as perceived greenness, derived from surveys but not whichever factor you desire to predict. If the goal is to predict soundscape pleasantness and it is necessary to survey people about the visual pleasantness, why not just also survey them about the soundscape pleasantness directly? Certainly this mix of perceptual data is useful in research and can elucidate the relationship between the sonic and visual environments, but it is not useful in a practical predictive context. Any results which arise from research combining this sort of perceptual information must eventually be translated into a component which can itself be measured or modelled.

Calculation – The second constraint is that any analysis of the measured data can be done automatically, without human intervention. If the eventual goal is to deploy the model on continuously-running, unmanned sensor nodes or to enable practical large-scale measurements, the predictive model should be capable of operating with minimal human input. This means, for instance that if the model includes information about the sound source, this identification of the source should be possible to do automatically (i.e. through environmental sound recognition).

A potential constraint for some applications is related to computation time. Since one proposed application of a predictive soundscape model is to embed the model on a WASN node, the model would then need to be able to run on relatively low-power hardware such as a Raspberry Pi with a reasonable latency. This would especially present an issue for those models which rely on the combination of several psychoacoustic features (such as Mitchell et al. 2021; Orga et al. 2021), since these features are computationally intensive to calculate and several of them may need to be computed for each time step of the model. Although this is a real practical concern that should be addressed in the future, for the sake of this initial definition of a general predictive model used across many applications, we have not considered this a strict constraint.

Generalisability – The third constraint is for the model to be generalisable to new locations. Ideally, it will be generalisable to new and (to it) unfamiliar soundscape types, but the minimum requirement should be that it can be applied to new locations which are otherwise similar to those in the training data. This means that any factors which are used to characterise the context provided by the location should be distinguished from a simple label of the location and should instead be derived from measurements of the location. In practice this could be geographical or architectural characteristics of the space, a proposed use-case of the space, or consistent visual characteristics of the space such as the proportion of pavement to green elements. This is in contrast to the model created in Mitchell et al. (2021) which was constrained to be used only on those locations included in the training data since it made use of a location label.

For this third point, some aspects of the first and second constraints can be relaxed. Since this would only need to be defined once for a location, definitions such as the use case of the space could be defined by the person using the model. What is necessary is that the model and its component location-context factors can be set up ahead of time by the user, then the recording-level effects are able to be calculated automatically. In a multi-level modelling (MLM) context (such as that used in (Mitchell et al. 2021), this essentially amounts to choosing the appropriate location-level coefficients ahead of time then automatically calculating the features which are fed into those coefficients (per constraint 1 & 2).

Robustness – Finally, the model should be robust to missing components. If the original or full construction of the model depends on demographic information of the population using the space, in cases where this information is not available, it should be possible to omit it and still obtain a reasonable result. Here we may define potential ‘must-have’ and ‘optional’ factors. Given the amount of variance explained by the various factors which have been considered in previous predictive models, in-depth acoustic information is a must-have, while demographic and personal factors are an optional factor where the trade-off of losing 3% of the explained variance in eventfulness (Erfanian et al. 2021) is accepted as reasonable. Based on the results of Mitchell et al. (2021), it would appear that location-context is crucial for modelling the pleasantness, but not for modelling the eventfulness. In order to determine the must-have factors for characterising the location-context, more work will need to be done to determine the appropriate input factors and their relative importance.

5 Making use of the predictions in design

There are various potential methods for integrating the predictive soundscape approach into a design and intervention setting. Not all spaces can or should have the same soundscape and soundscapes should be treated as dynamic, not static; identifying and creating an appropriate soundscape for the particular use case of a space is crucial to guiding its design. Proper forwardlooking design of a soundscape would involve defining the desired collective perception in the space. In the probabilistic soundscape approach from Mitchell, Aletta, and Kang (2022), this can be achieved by drawing the desired shape in the circumplex and testing interventions which will bring the existing soundscape closer to the desired perception. A soundscape may need to be perceived as vibrant during the day and calm for some portion of the evening, meaning the desired shape should primarily sit within the vibrant quadrant but have some overlap into calm. This also enables designers to recognise the limitations of their environment and acknowledge that it is not always possible to transform a highly chaotic soundscape into a calm one. In these cases, instead the focus should be placed on shifting the perception to some degree in a positive direction.

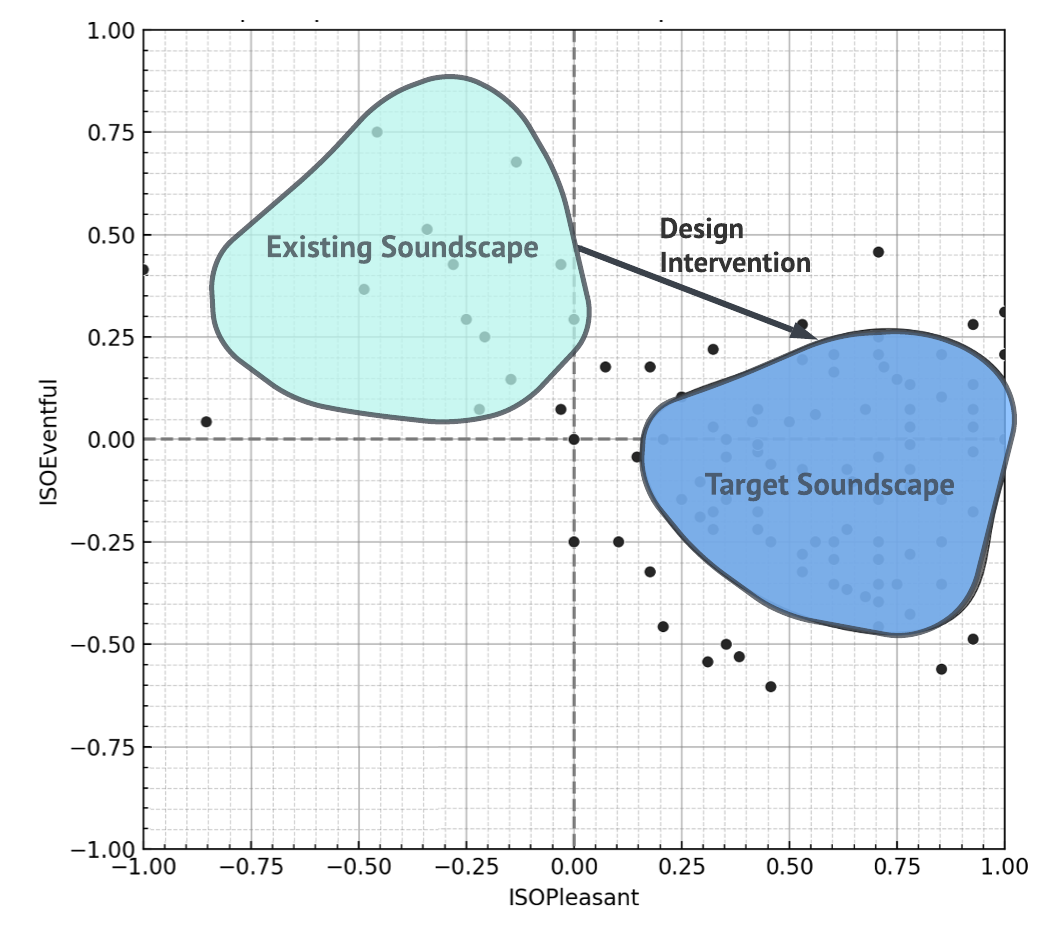

The most sophisticated method of setting design goals is therefore to identify the desired shape which represents the variety of desired outcomes, and focus on designs and interventions which are most successful in matching the predicted outcome with that goal. This strategy of defining the optimal soundscape as an area or a shape within the 2-dimensional circumplex was previously illustrated by Cain, Jennings, and Poxon (2013). In Figure 2, we have adapted Cain’s Figure 6 to show how the shape of a target soundscape can be set and the shape of the existing soundscape compared to it. The work of a designer is then trialling intervention options which move the design soundscape closer to the target soundscape.

6 Towards Soundscape Indices

Although the types of visualisations developed in (Mitchell, Aletta, and Kang 2022) and (Cain, Jennings, and Poxon 2013) are a powerful tool for viewing, analysing, and discussing the multi-dimensional aspects of soundscape perception, there are certainly cases where simpler metrics are needed to aid discussion and to set design goals. Within the practicalities of built environment projects, the consequences and successes of a design often need to be quantifiable within a single index. Whether to demonstrate performance indicators to a client or to set and meet consistent policy requirements, numerical ratings and/or rankings are necessary. This therefore necessitates the creation of consistent and validated indices which indicate the degree to which a proposal achieves a set design goal.

The challenge for creating a single number index lies in properly combining the two-plus dimensions of soundscape perception with the needs of a specific project into a single index. The obvious option would be to ignore the multi-dimensionality and only score soundscape designs on the basis of their pleasantness score (as done in (Ooi et al. 2022)). However, this seems to ignore both the significant importance of the eventfulness dimension in shaping the character of a soundscape and the role of appropriateness in determining the ’optimal soundscape’ for a space. Ideally, a soundscape index (or set of soundscape indices) would succeed at capturing all these aspects into a single scoring metric.

7 Conclusion

The existing methods for soundscape assessment and measurement, such as those given in the ISO 12913 series, have been focussed primarily on determining the status quo of an environment. That is, they are able to determine how the space is currently perceived, but offer little insight into hypothetical environments. As such, they are less relevant for design purposes, where a key goal is to determine how a space will be perceived, not just how an existing space is perceived. The methods for assessment outlined in ISO/TS 12913-2:2018 (2018) and for analysis given in ISO/TS 12913-3:2019 (2019) are inherently limited to post hoc assessments of an existing space. Since they are focussed on surveying people on their experience of the environment, it stands that the space must already exist for people to be able to experience. Toward this, and following from the combination of perceptual and objective data collection encouraged in ISO/TS 12913-2:2018 (2018), the natural push from the design perspective is towards ’predictive modelling’.

References

Reuse

Citation

@inproceedings{mitchell2023,

author = {Mitchell, Andrew and Aletta, Francesco and Oberman, Tin and

Erfanian, Mercede and Kang, Jian},

title = {A Conceptual Framework for the Practical Use of Predictive

Models and {Soundscape} {Indices:} {Goals,} Constraints, and

Applications},

booktitle = {INTER-NOISE 2023 Conference},

date = {2023-08-20},

url = {https://drandrewmitchell.com/research/papers/2023-08-20_Internoise-framework/InterNoise2023_Mitchell_Predictive_Model_Framework.html},

langid = {en},

abstract = {With the recent standardization of soundscape, there has

been increased interest in bringing the soundscape approach into an

engineering context. While traditional assessment methods, such as

those given in the ISO 12913 series, provide information on the

current status quo of an environment, they offer limited insight

into hypothetical environments and are therefore less relevant for

design purposes. This conference paper presents a conceptual

framework for the practical use of predictive soundscape models and

indices. The framework outlines the goals, constraints, and

potential applications of these models and highlights the need for

further research in this area to better understand the dynamics of

soundscape perception and to put predictive models to practical use.

Predictive soundscape models can be integrated with soundscape

indices - such as those being developed by the Soundscape Indices

(SSID) project - for assessment purposes, providing a comprehensive

approach to evaluating and designing sound environments. The use of

predictive models is necessary to address the challenges faced in

practical applications of the soundscape approach and to fill the

gap between traditional assessment methods and the design of sound

environments.}

}